Book review: Wild Company. The Untold Story of Banana Republic by Mel and Patricia Ziegler

Wild Company is the story of Banana Republic told by its founders, Mel and Patricia Ziegler. The authors manage to transmit the thrilling rhythm, their daily challenges, their motivations, and their enthusiasm.

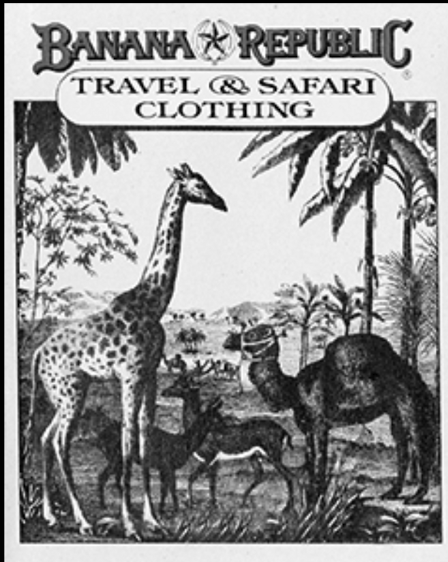

I was surprised by how different the original concept and branding was of what Banana Republic is today. Up to 1988, Banana Republic offered with great success safari and military-styled clothing. Starting with $1,500 dollars, the Zieglers bootstrapped the company building a solid brand and a loyal client base.

In 1983, Don Fisher, the Gap Company founder and CEO, discovered Banana Republic and approached the Zieglers with an offer to buy the business. Although Banana Republic was profitable at the time, had an above average hit rate for their catalog sales, they had only two store locations. They needed desperately funding to grow and hire professional help to run the operations.

Part of the deal was that both Mel and Patricia Ziegler—the founders and owners—would remain for five years managing the company. What do I know about your business? was Don Fisher’s reasoning. As long as they remained profitable, they could count on the Gap financing and helping with whatever they needed to run the company.

During those five years, thanks to the brilliance and commitment of its founders, and the financial and operational support of the Gap, Banana Republic grew to become one of the darlings of retail and adding real value to the Gap bottom line.

At one point, Fisher decided to involve his son Bob in Banana Republic. While Patricia and Mel Ziegler were creatives and bold, for Bob everything was about the data. He didn’t understand fashion, nor that Banana Republic was not the Gap nor in the copying business but setting fashion trends. It also was not for the big public. Bob Fisher focus on the short-term and profits over the long-term vision was a constant cause of friction with the founders. Their relation was not great, but they managed to go along.

Around 1988, after the markets collapsed on Black Monday and the Gap leadership began feeling the pressure from stakeholders and the “expert” opinion of Wall Street analysts, Dan Fisher decided to hire Michael Drexler as the CEO for the Gap.

Drexler didn’t care if Banana Republic was one of the jewels of the crown and that it was a growing, solid business. In his worldview, a company like Banana Republic was not “optimized” for the world of serious retail. It didn’t help that the Zieglers were the antithesis of corporate government, and Mel Ziegler defined himself as unemployable.

Some months after Drexler appointment, Don Fisher invited the Zieglers to a meeting. They were surprised to find Mickey Drexler instead. Patricia was holding their one-week old newborn. Drexler announced the Zieglers communicated that they were to report directly to him, and that he was taking direct control of Banana Republic. Patricia was expected to travel immediately to Paris to copy the best stuff she see saw there on the stores.

Mel simply said: “It’s not going to happen, Mickey”. Both Zieglers resigned and left the company.

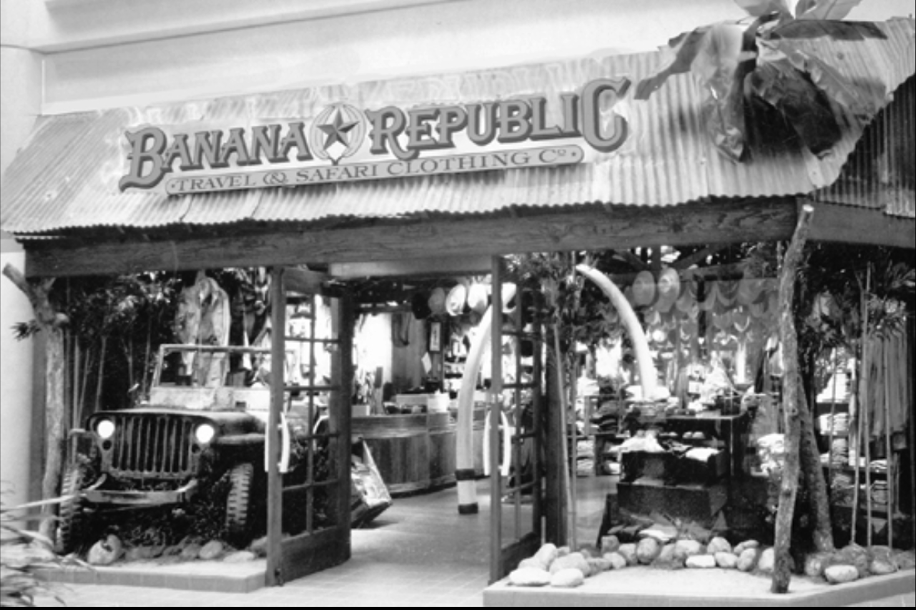

Under Drexler supervision, Banana Republic went through a complete transformation, dropping the signature design and style that had made the company successful and famous. Many Banana Republic’s employees resigned en masse. Drexler hired and fired five successive design teams. The carefully tailored catalog with hand-drawn illustrations was replaced by the standard models portraying clothes used in the industry. The stories in the catalog were removed. Banana Republic stores, which were designed on a one by one basis, were redesigned to look like conventional, cost-efficient stores . The jeeps, tents, and tusks were yanked from the stores and replaced by neat white shelving.

The results of Drexler’s strategy didn’t wait too much:

For several years, the trio [Don and Bob Fisher, and Mickey Drexler] found themselves explaining to analysts time and again that they never expected the sheer volume of negative reaction they got from incensed Banana Republic customers offended by the abrupt changes in the stores and catalogues. The repositioning became an apologetic “turnaround.” Ultimately, after nearly a decade of thrashing about, Banana Republic was slotted, in the official lingo of the Gap annual report, into an “accessible luxury concept” with “higher price points” than Gap. (p. 192)

What happened to Banana Republic under the Gap is another example of how a narcissistic, profit-first driven leader can destroy an organization, brand and culture in a short time, and even so exit the company years later as if he were the great savior.

Of course, the story is told by the founders whose brand was destroyed by corporate management. So you can expect that the book tells only one side of the story. For example, the Zieglers failed completely at understanding Bob Fishers worries about growth and profit, even if his proposals were not sound. After the appointment of the new CEO, they didn’t even considered approaching Drexler, understanding his point of view (or at least getting to know it). They declined Drexler’s request to share office spaces with Banana Republic.

Don Fisher passive attitude also is to note. During the first five years after Banana Republic’s acquisition, he had the wisdom to let the Zieglers be and do what they did best, while offering the expertise of the Gap for running the operation. But it was clear that Banana Republic, could not be managed with the same criteria as the Gap. The companies cultures were very different. But he did nothing to ease the transition besides appointing his son Bob vice president of merchandising. Bob character was so gloomy, demotivated, and negative that his family called him “Nego”. But Fisher wanted his son in the business, even if the Gap was a publicly traded company.

A good read. Rating 5/5.

PS: After posting the review, Luis pointed me to Abandoned Republic, A Journey Throught the Vintage Banana Republic Catalog. A great complement to the book.