The Great Mental Models (Vol. 1), by Shane Parrish

Shane Parrish was a cybersecurity expert at Canada’s top intelligence agency when the world suddenly changed on September 11, 2001. He “was thrust into a series of promotions for which I had received no guidance, that came with responsibilities I had no idea how to navigate.”

While going through and MBA program and looking for mentors, he discovered Charle Munger, the billionaire business partner of Warren Buffet at Berkshire Hathaway. “Munger has a way of thinking through problems using what he calls a broad latticework of mental models, (…) chunks of knowledge from different disciplines that can be simplified and applied to better understand the world.” He started documenting his learning on his blog, Farnam Street.

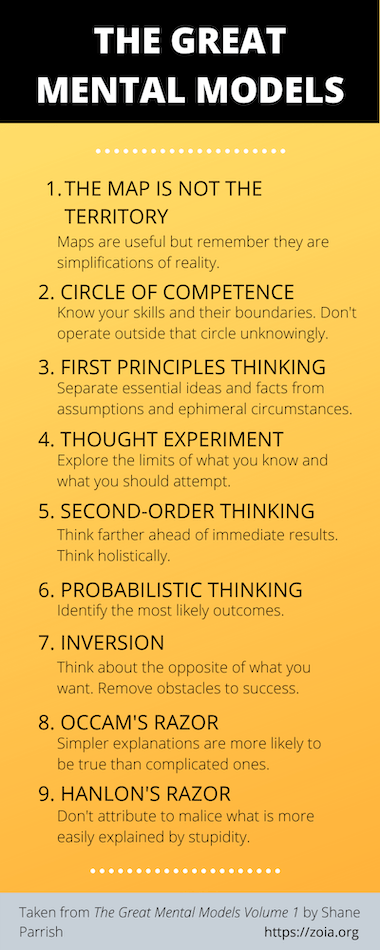

The Great Mental Models Volume 1: General Thinking Concepts is the first in a series of books by Parrish about timeless, broad ideas “to allow others to approach problems with clarity and confidence, to make their journey through life more successful and rewarding.” This volume describes 9 mental models about general thinking that will “improve the way you approach problems, consider opportunities, and make difficult decisions.”

1. The Map is not the Territory

Maps are limited but useful representations that reduce complexity to simplicity. The goal of a map is not simplification but understanding. However, don’t forget that maps cannot be everything to everyone. Good maps are created and updated by explorers of the territory, who reflect their values, standards, and limitations on the map. Maps cannot be everything to everyone.

For example, supply and demand curves may be useful for a general understanding of price flexibility and customer behavior. But it’s certainly a simplification of how customers behave.

2. Circle of Competence

A circle of competence is the subject area which matches a person’s skills or expertise. True knowledge of a complex territory cannot be faked. Within our circle of competence, we know exactly what we don’t know. We know what is knowable and unknowable.

Don’t take your circle of competence for granted, nor operate as if it were static. Curiosity and a desire to learn, either from yourself (slow) or others (more productive) are essential. Track your record, monitoring honestly so you can use the feedback in your advantage. Go to people you trust to ask for feedback. We have too many biases to rely only in our own observations.

Most important of all, know the boundaries of your circle of competence, so you don’t operate outside of it without noticing. When consciously operating outside your circle of competente, learn at least the basics of the new realm without falling into unwarranted confidence.

3. First Principles Thinking

First Principles thinking clarifies complicated problems by separating the underlying ideas, facts, and non-reducible elements, from any assumptions based on them. What remains are the essentials. “When you really understand the principles at work, you can decide if the existing methods make sense. Often they don’t.”

Methods to separate the essential from the accidental include Socratic Questioning , which “stops you from relying on your guts and limits strong emotional responses”:

- Clarify your thinking and explain the origin of your ideas.

- Challenge assumptions. Why do I think this is true? What if I though the opposite?

- Look for evidence. Question the sources.

- Consider alternative perspectives. What do others think? How do I know I’m correct?

- Examine consequences and implications of being right, but also of being wrong.

- Question the original questions.

Another method is asking the 5 Whys, where the goal is to land on a what or how. “It’s about systematically delving further into a statement or concept so that you can separate reliable knowledge from assumption.”

Sometimes we don’t want to fine-tune what is already there. We are skeptical, or curious, and are not interested in accepting what already exists as our starting point. So when we start with the idea that the way things are might not be the way they have to be, we put ourselves in the right frame of mind to identify first principles. The real power of first principles thinking is moving away from random change and into choices that have a real possibility of success.

4. Thought Experiment

Thought experiments are “devices of the imagination used to investigate the nature of things (…) to understand the situation enough to identify the decisions and actions that had impact.” They let us explore the limits of what we know and the limits of what you should attempt. Uses of this model include imagining physical impossibilities, re-imagining history, and intuiting the non-intuitive.

Thought experiments help us learn from our mistakes and avoid future ones. They let us take on the impossible, evaluate the potential consequences of our actions, and re-examine history to make better decisions. They can help us figure what we really want, and the best way to get there.

Albert Einstein was a great user of the thought experiment. “One of his notable thought experiments involved an elevator. Imagine you were in a closed elevator, feet glued to the floor. Absent any other information, would you be able to know whether the elevator was in outer space with a string pulling the elevator upwards at an accelerating rate, or sitting on Earth, being pulled down by gravity? By running the thought experiment, Einstein concluded that you would not.”

5. Second-order Thinking

Second-order thinking teaches us two important concepts. First, if we are interested in understanding how the world works, we must include second and subsequent effects. Also, we must be observant and honest as we can about the web of connections we are operating in.

Areas of application include prioritizing long-term interests over immediate goals, and constructing effective arguments.

“(…) any comprehensive thought process considers the effects of the effects as seriously as possible. You are going to have to deal with them anyway. The genie never gets back in the bottle. You can never delete consequences to arrive at the original starting conditions.”

Warren Buffett used a very apt metaphor once to describe how the second-order problem is best described by a crowd at a parade: Once a few people decide to stand on their tip-toes, everyone has to stand on their tip-toes. No one can see any better, but they’re all worse off.

6. Probabilistic Thinking

“Probabilistic thinking is essentially trying to estimate, using some tools of math and logic, the likelihood of any specific outcome coming to pass.”

Effectively applying this model implies basic understanding of bayesian thinking (using relevant prior information in making decisions), conditional probability (taking in account the conditions that precede the event you want to understand), and fat-tailed curves. Also, considering the probability of your probabilities —the meta-probability—, and possible asymmetries (i.e., projects are most often late than ahead of time).

Part of this mental model is recognizing the possibility of black swans. Preparing and benefiting from volatility involves seeking out situations that we expect have good odds of offering us opportunities (“upside optionality”), and learning to fail properly by developing personal resilience to learn from failures and start again. “Whenever possible, try to create scenarios where randomness and uncertainty are your friends, not your enemies.”

7. Inversion

Inversion means approaching a situation from the opposite end of the natural starting point. Think about the opposite of what you want. Combining the ability to think forward and backward allows us to see reality from multiple angles.

To apply inversion, assume that what you are going to prove is either true or false. Then show what else would have to be true for that to happen. Also, think deeply, from different angles, what you must avoid to achieve your goal. It implies shifting from “how do we fix this problem” to “how do we stop it from happening in the first place”.

Another approach to inversion is called the Kurt Lewin’s process. Identify the forces that support change towards your objective, and the ones that impede change towards it. Then strategize by augmenting supporting forces, or reducing impeding ones.

8. Occam’s Razor

This model states that simpler explanations are more likely to be true than complicated ones. While sometimes things are simply not that simple, most of the time, “instead of wasting your time trying to disprove complex scenarios, you can make decisions more confidently by basing them on the explanation that has the fewest moving parts.”

“Take two competing explanations, each of which seem to equally explain a given phenomenon. If one of them requires the interaction of three variables and the other the interaction of thirty variables, all of which must have occurred to arrive at the stated conclusion, which of these is more likely to be in error?“

Occam’s Razor can be applied in leadership. “When Louis Gerstner took over IBM in the early 1990s, during one of the worst periods of struggle in its history, many business pundits called for a statement of his vision. What rabbit would Gerstner pull out of his hat to save Big Blue? (…) His famous reply was that the last thing IBM needs right now is a vision. What IBM actually needed to do was to serve its customers, compete for business in the here and now, and focus on businesses that were already profitable. It needed simple, tough-minded business execution.”

9. Hanlon’s Razor

“We should not attribute to malice that which is more easily explained by stupidity.” This model helps us avoid paranoia and ideology. It helps us look for options instead of missing opportunities. “When we see something we don’t like happen and which seems wrong, we assume it’s intentional. But it’s more likely that it’s completely unintentional.”

I would recommend this book to anyone trying to improve her or his thinking and decision making process.

(Este artículo también está disponible en castellano: The Great Mental Models, Vol. 1, por Shane Parrish).